Artist's Statement

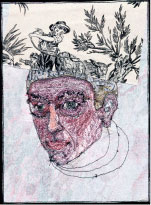

I hack machines in order to draw with them. That is, I use an industrial zig-zag sewing machine to draw with thread into fabric. Since 2013, I have also used a computerized embroidery machine and CAD software. This is a makeshift, hybrid art form, employing materials and machines meant for the manufacture and ornamentation of clothing, along with hand tools like pliers and screw drivers, not customarily used for drawing. In 2010, I began to include text, at first appropriated, now I usually write it and sew it out. My drawings always tell stories; even without words, there is always a narrative. Though drawing with machines is exacting work, I have given myself over to it, becoming as much an instrument of the process as any of the machines. Drawing in this way has transformed, reconfigured, re-imagined many kinds of fabric, even contemporary tapestry copies of 14-20th Century paintings, subverting the original imagery and narrative. See for yourself.

I buy fabrics and trim in fabric stores in New York City and wherever else I happen to be. People who know my work offer fabric, buttons, needlework, and trim, occasionally from dead relatives. I almost always welcome it. Sometimes I incorporate leftovers from my years as a sculptor and maker of works on paper, including fabric silk-screened with images of my old line drawings and paint-smeared work pants from the early 90s. Having used all kinds of power tools as a sculptor, I much prefer drawing with an industrial sewing machine to hand-sewing. My eyes in close-up glasses, my face six inches from the moving needle, I have an intuitive bond with the machine. At the start, I have no idea what a drawing will look like. But ideas just get in the way. The key is to give myself over to the process.

That said, I am after as complex a truth as possible. My drawings reflect the world in all its glory, horror and absurdity, its workers and slugs, sleepwalkers and prophets. Who is in charge and who suffers because of that? Why does the past keep biting us in the ass? What does it mean to be in love? I do my best to make sense of things, and it takes everything I've got.

How I Started Drawing With an Industrial Sewing Machine

I was trained and worked as a sculptor, but always drew.

In 1992, a series of my works on paper that combined pattern and figure took on a life of its own, and since then I have mostly drawn. But in December of 2000, my drawings told me that they had to be sewn, and it wouldn’t be enough to hand-embroider them: I would have to buy a sewing machine and learn to generate and control a sewn line. So I bought a portable sewing machine and began to learn to draw with it, at first simply, then with greater complexity, making contemporary drawings that were enriched and transformed by the process of their creation. From the outset, I somehow knew that this was what I was going to do for the rest of my life and that the potential was enormous. I wanted to make the sewing machine an extension of my nervous system.

In the summer and fall of 2001, as my drawings grew bigger and more complex, with layered fabric and areas of dense sewing, the little sewing machine began to falter, breaking thread and tying knots instead of making stitches. Most days, it malfunctioned every few minutes, which greatly slowed and complicated the drawing process.

It took months to find a better machine and a dealer who could provide adequate technical support, but in March of 2002, I finally bought a Consew 2033R, an industrial zig-zag sewing machine that would sew almost anything I gave it. I also had to replace the Consew’s clutch-based motor with an electronic motor to compensate for my damaged feet, which lack proprioceptive capacity. In response to the power of the Consew and the exquisite control afforded by the electronic motor, my drawings changed so much - for the better - that everything I’d done up to that point suddenly seemed the work of another person.

On the strength of the first four drawings I created on the Consew, the Luise Ross Gallery, then in Soho, now in Chelsea, agreed to represent my work. Since 2002, my drawings and books have been shown all over the United States and in Europe. In the last three years, there have been two solo museum exhibitions of my drawings. I recently bought a second Consew, so that I would never be without a functioning sewing machine.

Why I Make One Of A Kind Books

Dream Girls (2007)

click to view video (at blip.tv)

Book of Lives (2008)

click to view video (at blip.tv)

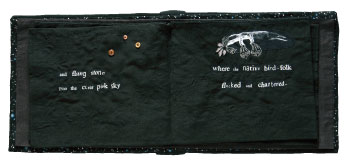

The Second Black Book (2009)

click to view video (at YouTube)In 2007, when Esther K. Smith, a book artist (www.PurgatoryPiePress.com) who is a fan of my work, needed a little fabric book to be photographed for a how-to-book she was writing for Random House, I was persuaded to make a book—really only because Esther kept asking.

Crude as it was, my first book, Dream Girls was a revelation, a somewhat approximate object that when opened contained whole worlds! There was something so uncanny about my medium and imagery in book form that I resolved to make at least a book a year for the rest of my life. In 2008 I made two: A Book of Horses and Book of Lives. My first three books were wordless contemporary illustrated manuscripts.

But my process requires me to be open to chance, and one morning in the spring of 2009, while walking my dog, I found a big black broken umbrella on the sidewalk and took it home because its black fabric was printed with mostly white text. I cut the printed fabric off its twisted skeleton and put it away. Eventually it occurred to me that if I were to use white ink to print a few silk screens with text from earlier art projects onto black fabric, I would have a store of words that I could draw from as I do my store of patterned scraps.

And so I did. Out of printed and found text, I made two books in 2009. The First Black Book had only text. The Second Black Book had more text and a few essential illustrations. In the summer of 2010, I finished Pressing Questions, a new book that combines re-purposed fancy colored text, wholly constructed letters, and substantial visual imagery. The book that I make next year probably won't look much like any of these.

How My Work Fits Into The Larger Context of Contemporary Art

I am an appropriationist and a synthesizer, influenced by manga, anime, and other contemporary Asian art, as well as almost by everything else I see and hear, touch and taste. Appropriationists are everywhere in the contemporary art world. There are also many artists making sewn art, by hand and/or by machine. Some of it is considered painting and is stretched accordingly, other sewn pieces are constructed, knotted, knitted, and/or waxed, emphatically dimensional and sculptural. I myself never stopped drawing, even after I changed my medium. I still hang my drawings naked on the wall, like a work on paper, even though the bigger my drawings are and the more intensively sewn, the more they wrinkle, sag, and bulge expressively when pinned to the wall. The majority of contemporary sewn art references sewing. Mine doesn't. It is a gaudy hybrid, process-directed contemporary art whose appearance is both a result of the way it is made and despite the way it is made.

In November of 2010, I began a still-ongoing series of drawings that use self-generated text as well as hybridized imagery. Again, many contemporary artists make use of text in their work. But with the strong dramatic arc of my narratives and the figures I create as distinct characters, my recent drawings have most in common with animé and other popular contemporary animation, video, and comics. Human beings have an enormous appetite for narrative; they trade gossip, watch soaps, read comics, study history.

My narratives offer viewers an alternative to the tired stories so often found in films, video, books, and new media, which recycle and re-work whatever worked last time. My drawings and books represent a new model for storytelling, an opportunity for the public to experience rich, complex, and relevant narratives by means of a direct immersion in my art. And people do not necessarily have to understand everything they experience to be served by it.